The streets are absent of traffic, there’s not a foreigner in site, and no vendor is actively touting — only 20km away from Guilin, a Chinese city of 5 million inhabitants. Founded in the Song Dynasty, Daxu’s structures date back to the Ming and Qing dynasties (source: Chinese travel websites). Strategically located on the northern bank of the Li River, the town was a flourishing commercial hub during the Ming Dynasty. Today, Daxu is a tranquil non-touristy respite from Guilin and home to local artisans and farmers who carry on some of the same crafts as their ancestors.

Local vendors and townspeople whom I passed all met my eyes with a smile or nod. If I said “nihao,” they promptly returned the greeting, evincing more enthusiasm with age. When I asked this vendor where her battered fish were from, she motioned to the Li River bank 100m away from her stall.

Baskets of live critters – crabs, lobster, and prawns – crawled frenetically in plastic buckets flanking the fried food stalls.

Pedestrian-only flagstone streets define Daxu’s historic core. I only saw locals walking a short distance without rain cover to their house or shop. The exception was one bamboo raft full of Chinese tourists with umbrellas roaming the streets.

Daxu’s residents keep their doors open and casually look outside in acknowledgement of passerby. The households I peeked into had TV sets in spartan front rooms and plastic fly swatters lying about. The living space above had the most luxurious decor. Outside, laundry was draped over hanging bamboo poles and electrical lines ran at roof awning level.

I paused at this vantage point for a few breaths, taking in that this was a real place with families living behind each wooden wall. In my imagination, a still out of The Red Lantern had materialised into this street.

One of the open doors fronted an art gallery. My Nihao call was met by silence, so I wandered in a few steps past the doorway. The sketching style was original with the theme of elephant profiles.

This studio lured me in by blasting classical music. The artist used an iPad to outline a bridge scene onto a blank canvas.

Always on the quest for instruments and musicians, I caught sight of a Guzheng, a Chinese traditional plucked string instrument. I browsed the shop’s art while eyeing the Guzheng and after some time asked if I could play it. The artist obliged and taught me how to pluck on the player’s right side while bending the strings on the left. The notes follow the pentatonic scale, and almost any melody or rhythm sounds pleasant to the ears. We traded the instrument back and forth solely interacting through music, no words. He would resume painting as I played. I found it difficult to strum at a constant frequency the way he did, similar to picking on a mandolin. He brought out a small stone pick with tape that he circled around my finger, but I was still challenged to mimic his style.

I purchased a few vivid paintings of bridge and river scenes. He packaged them in cardboard paper and with broad brush strokes painted calligraphy that read “Daxu. Guilin. China” and stamped his name in red ink.

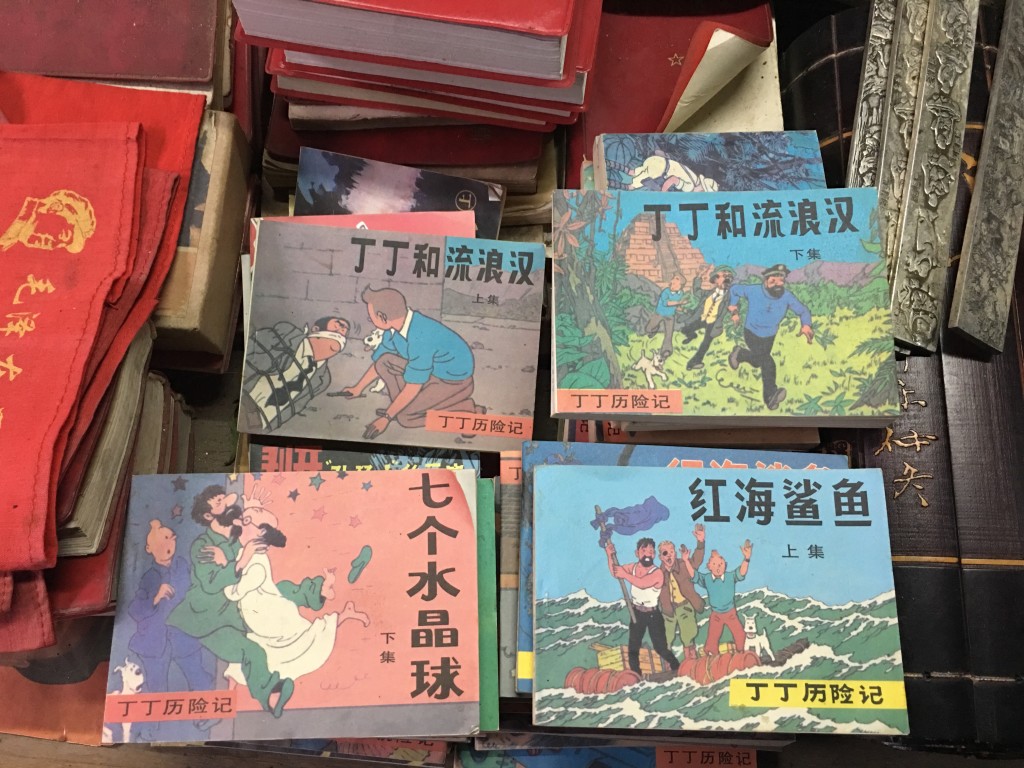

Another shop had a book section that surprisingly included my childhood favourite comic, Tintin by Hergé, sold in the style of a cheap flip book. The inventions that transpire in the absence of copyright infringement laws can be entertaining. From the cover I learned my first and only Chinese character “Tin.”

This bridge stood through the ages, as if sagging only a few cm with each dynasty.

The other side of the bridge was equally immune to the passing of time. It was anachronistic like a Kurosawa set. There were just enough people out to not give the appearance of a ghost town. I imagined a bell chiming, bringing everyone out to the streets like in a Western film.

An entrepreneurial homeowner offered a tour of his family’s home for 10 RMB ($1.53). He explained his ancestors had been merchants and landowners, and I gathered it had been in his family for at least 5 generations. In the front room, he proudly pointed out the swallows chirping from a nest in the rafters.

The bed had a traditional Chinese structure lined with artwork. Unfortunately I didn’t notice the erhu hanging on the wall until after I reviewed my photos, or I would have asked if they or I could play it.

The kitchen featured a wooden cutting board, rusted knife, canteen, baskets of firewood, and a fireplace for cooking.

The courtyard stones, intersected by plant growth, were assembled in a pattern of 3 curved shapes for good luck. A window across from the kitchen had an abacus used for paying farmers back in the day. The spaces were designed to receive natural light.

The man ended the tour by asking me what I thought of Tulumpu, whom he clarified was “the next Obama.” When I understood he was referring to Trump, I told him “don’t like” in Chinese. He inquired why, and I translated on my phone “because he is racist.” He nodded in what I interpreted as agreement.

A welcoming sign surrounding by red paper advertised “My Family Hotel,” the only English lettering I saw in town.

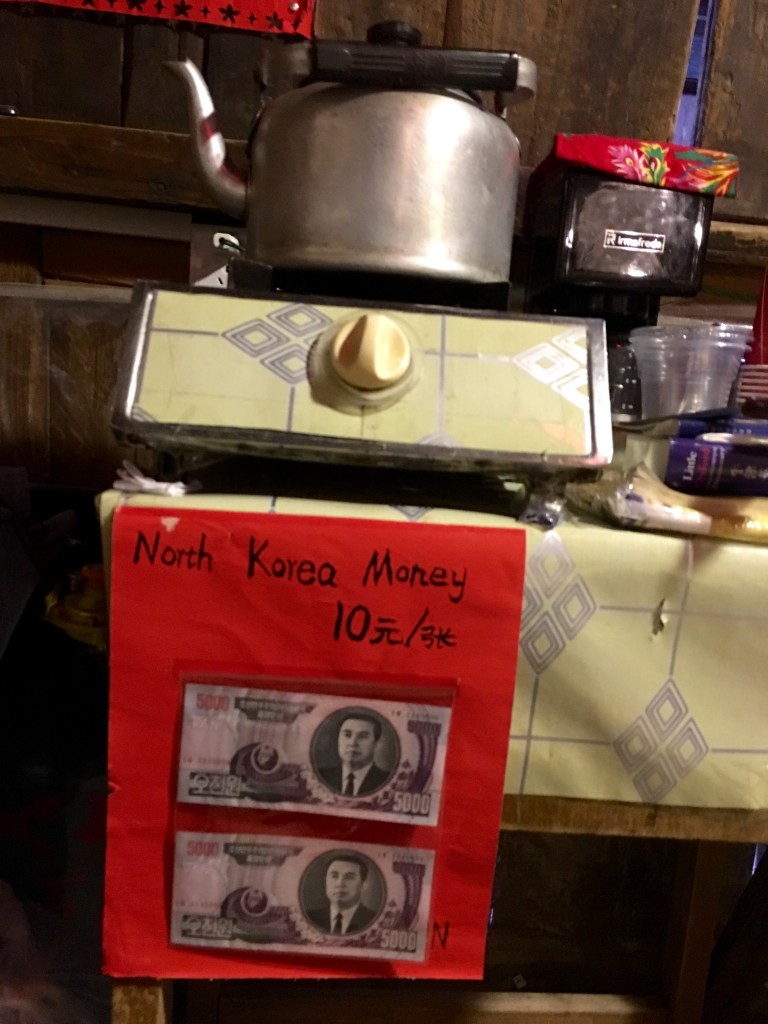

Inside there was food, drink, and random international currency for sale. I traded 10 RMB for a North Korean 5000 won bill, unsure of where I’d be able to find one elsewhere.

I ordered sweet and tangy pomelo tea and mung bean cake which flaked apart like loose halva. After serving me, the hotel owner invited me to eat wok-sautéed goose leg and green beans she had prepared for her and her husband for 10RMB. It was mouth watering and fresh from the river. In basic Chinese, we discussed where they were from, what brought me to Daxu, and how I would get back to Guilin. I wrote for a little while in the pleasant hotel space as they quietly finished the bottom of the wok.

On my way out of town I took the inland route through backyard farms and followed a farmer biking with a loaded cart of neatly bundled leafy green vegetables. On mild uphills, he had to dismount his bike and walk. I helped push from behind until he reached flat ground, and he returned the favour with the most grateful toothless grin I’ve seen.

Very nice pics of the city and the surrounding agricultural land. Wonder if the river is clean for fishing?

Wonder if Tintin is the same story or do they change the story?

I tried not to think about river cleanliness. On the Li River passenger boats, they dunk the cut chunks of fish over the stern to clean them before deep frying in a wok.

I bought Tintin and the Red Sea Sharks. From looking at the pictures it seems to be the same story, but one leaflet is only part of the story, not the whole book.